Increased Suicide Rates Coincide with Opioid Addiction

Mady Ohlman stood in a friend’s bathroom looking down at the sink, where she had set up numerous needles filled with heroin.

She intended to inject them all. After the first few, she collapsed and lay drugged-out on the floor.

The 22-year-old addict later recalled being angry when she could still get up. She wanted to be dead.

For her, suicide seemed a painless way out.

“You realize getting clean would be a lot of work,” Ohlman said. “And you realize dying would be a lot less painful. You also feel like you’ll be doing everyone else a favor if you die.”

Ohlman has now been clean for more than four years. But she believes many drug users hit the same low point she did: When the addiction and the pursuit of illegal drugs crushes their will to live.

According to a recent report by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), at least 40 percent of active drug users wrestle with mental health issues, increasing the risk of suicide.

Suicides on the Rise

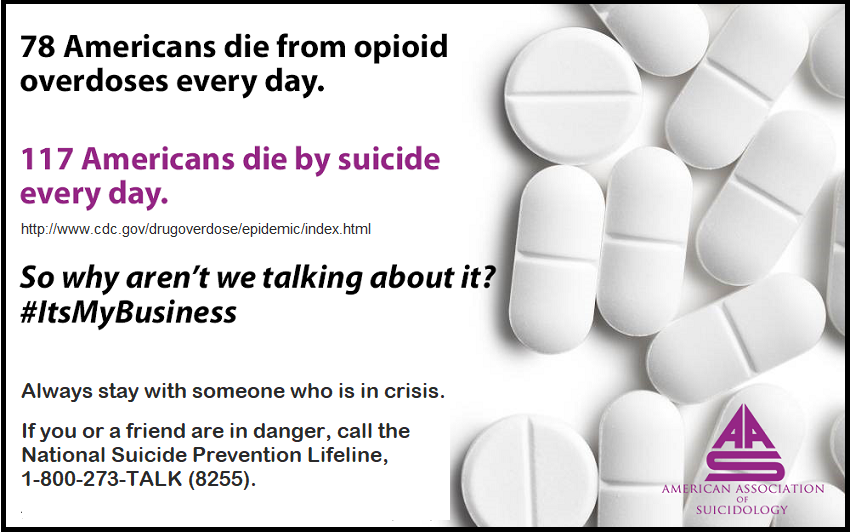

Earlier this year, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) released the alarming results of its most recent study of suicide in this country. According to the report, U.S. suicide rates have increased in nearly every state over the past two decades. Even worse, half of the states have seen increases of more than 30%.

These suicide figures coincide with the dramatic rise in opioid addiction which some experts say can’t be overlooked. The CDC has calculated that suicides from opioid overdoses nearly doubled between 1999 and 2014.

In addition, data from a 2014 national survey showed that opioid addicts were 40% to 60% more likely to contemplate suicide than the general population. And habitual users were twice as likely to attempt suicide as nonusers.

An earlier National Institutes of Health (NIH) study found that, compared to the general population, opioid drug addicts are 13 times more likely to exhibit suicidal behavior.

Seeking a Connection

However, untangling accidental overdoses from intentional deaths can be difficult.

Dr. Maria Oquendo is the past president of the American Psychiatric Association. She acknowledges that the opioid epidemic is occurring at the same time suicides have hit a 30-year high. And she believes that between 25% and 45% of deaths by overdose may actually be suicides. However, she says, few doctors look for that connection.

“They are not monitoring it,” Oquendo said. “They are probably not assessing it in the kinds of depths they would need to prevent some of the deaths.”

But that may be changing. A few hospitals in Boston, for example, are starting to ask every patient about substance abuse and whether they’ve considered hurting themselves. In doing so, they’re attempting to resolve the “chicken-and-the-egg” dilemma. Namely, “Do patients have mental health issues that lead to addiction, or did a life of addiction then trigger mental health problems?”

It’s also very difficult for health officials to determine a deceased person’s true intent, according to Dr. Monica Bharel, head of Massachussett’s Department of Public Health. “For one thing, medical examiners use different criteria for whether suicide was involved or not,” Bharel says.

As a result, there’s little data to go on right now, said Dr. Kiame Mahaniah, a Massachusetts family physician. That’s why he believes it’s important to provide treatment that “covers all those bases.”

Tackling the Despair

Addiction experts agree that recovery programs must work to tackle the despair that often accompanies substance abuse. In doing so, they can help patients acquire (or reacquire) a sense of purpose.

A big part of Mady Ohlman’s recovery, for instance, involves building a supportive community. For her, that means “meetings, 12-step, sponsorship and networking, being involved with people doing what I’m doing,” she said.

There’s a fatal overdose at least once a week within her Cape Cod community, she said. Some are accidental… others are not.

![logo2 258x300 logo2 258x300]() Want to Know More?

Want to Know More?

For more information about suicide and suicide prevention, download the CDC’s Fact Sheet.

If you need help or know someone who does:

Call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline toll-free at 1-800-273-8255, 24 hours a day, seven days a week, or visit suicidepreventionlifeline.org.

Want to Know More?

Want to Know More?